Duwarra Wujara

Two Young Men

Yanyuwa, Northern Territory - 2023

Two cousins are taken on the adventure of their lives.

In the time of the Dreaming, the Australian Aboriginal period of creation, two young cousins become Duwarra Wujara, newly initiated young men in the clans of their people. Frustrated and impatient, these two cousins abandon their duties in search of adventure… and mischief. The cousins journey far into the west, laughing as they go about breaking laws, killing animals and fouling traditions. But the boys are not alone, for Bujimala, the Rainbow Serpent has his eyes on them, ever vigilant as the guardian of this country. As he stalks the boys, he becomes frustrated with their antics. In a moment of despair, he swallows the boys and carries them far beyond the safety of their own country, hoping to scare some sense into these two teasing cousins. As they all travel, the country is named, bringing each place into Law.

These places are sacred to the Yanyuwa people to whom this story belongs. For hundreds of years the Yanyuwa people have expressed their identity through the oral traditions of song, poetry and story. Passed down from generation to generation, Duwarra Wujara is just one of these ancient traditions. Performed in the Yanyuwa language; an endangered dialect with only a handful of speakers. Duwarra Wujara is a warning to the young and adventurous.

Like so many Indigenous communities around Australia, the Yanyuwa people of Borroloola are faced with the looming reality of language and cultural extinction. In the time Co-Director John Bradley has been working with Yanyuwa elders, the number of fluent speakers has dropped from a few hundred to just three. This cultural crisis has led Yanyuwa elders to adopt alternative ways of passing down their knowledge to the coming generations. A woman in her nineties, Yanyuwa elder Dinah Norman a-Marrngawi, is old enough to remember the “old ways” of her ancestors. Wishing to share her love of culture, she has translated this story for the screen, a story passed down the generations for hundreds of years.

Duwarra Wujara is a traditional narrative for the creation of law and country. It is a story full of meaning and message, of the interconnectedness of people to Country, of the living world around us and what it means to be part of a community. But it is also entertainment, meant to capture and engage the hearts and minds of not just Yanyuwa, but people from all cultures and all ages.

Q&A

How did the opportunity to tell this story come about?

Co-Directors John Bradley and Brent D McKee have been working together since 2007. At that stage John had spent 25 years working with Yanyuwa elders in Borroloola, learning their language, culture and practices. Over that period he had watched the language use begin to fade as elders passed and younger generations left Borroloola for work and other opportunities. Amongst the Yanyuwa elders, the original idea to tackle this crisis of culture was to produce a graphic novel of all the Yanyuwa Dreaming stories in the hope of sparking interest in younger generations still in Borroloola. This collaboration was the foundation for the animation as the graphic novel essentially served as the rough storyboards for several animations that the duo would produce.

After several years working outside Yanyuwa with various other indigenous communities around Australia with Wunungu Awara, the team traveled back to Borroloola in 2017 to begin story development with Dinah Norman on what would become Duwarra Wujara.

For people who are unfamiliar with the term, can you explain the Dreaming, and what its significance is to this film?

The answer to this question would differ greatly depending on where you are in Australia; broadly speaking the Dreaming (or Dreamtime) is the period of creation for Aboriginal Australians. The Dreamings shaped the country, customs and laws for the hundreds of different Aboriginal cultural groups around Australia.

Specific to the Yanyuwa, Dreamings are ancestral beings who can take many forms, birds, animals, fish, insects, and natural phenomena, they brought the original meaning to Country. They are not gods, they are kin to the living Yanyuwa families today. The Dreaming also created the political landscapes that still function today in the form of four patrilineal land owning clans. All Yanyuwa men and women belong to one of these four clans and each one of these groups have a number of Dreaming Ancestral Beings that are kin. The Dreaming is not a past event, it is ever present, living simultaneously within the past, present and future, and embedded in the Country itself. For Duwarra Wujara, we are dealing specifically with the Dreaming seen through the Yanyuwa lens. A few examples of this from the film are the lice that turn to stone on the beach, they are still there, they are the lice Dreaming. The hill that forms from the ground oven, it is the quail Dreaming. The well the boys dig out, the hole the serpent creates when it first emerges and two islands where the boys are left out at sea. They are all still there and the power of the Dreaming is still there with them. They are places of significance to the Yanyuwa people and it is tied in with the Law of their culture.

It is a period that can often defy conventional logic, especially when seen through a Western lens. Events can happen spontaneously without anything to precede them, often new characters will emerge without any pretext and disappear as quickly as they came. These often perplexing happenings were part of many early discussions about the Dreamings portrayal in the Duwarra Wujara. To Western eyes the young Mawurrinya’s spontaneous ability to create two trees out of nowhere could be quite jarring, or the sudden appearance and disappearance of a white Eagle towards the film's crescendo could be quite confusing. Where did these abilities and new characters come from and what do they mean? To Yanyuwa eyes, particularly the eyes of elders like screenwriter Dinah Norman, they are simply the Dreaming. In some cases things can happen that defy logic and that is just the way it is, in others the sudden appearance of a character speaks to the much larger anthology of interconnected stories that make up the cultural Law for Yanyuwa people. Several scenes within the film are examples of these interconnected stories. The Whirlwind Rainbow Serpent is on his own journey, from east to west and meets Bujimala on the river as he heads north. Similarly the white Eagle has its own Dreaming with the collection of a few wayward bats being only a small part of it. This interconnection is part of the larger complexity of Yanyuwa knowledge that is embedded in narratives like Duwarra Wujara, and what might be seen as a standalone event to an outsider is actually part of a rich tapestry.

This film is a Yanyuwa Dreaming, it is an honest and accurate representation of the sacred, complex and spontaneous period of creation that is the Dreaming, and an example of a vibrant and rich culture with a unique approach to storytelling.

Yanyuwa language and culture is central to the film, tell us about how that influenced the visual design of the film?

In the very early conversations, John had collected all the known animated depictions of the Dreaming and showed them to Dinah and other senior Yanyuwa. These examples were all very abstract in design, many incorporating Aboriginal art traditions in their visual design. Up until the 1980’s the Yanyuwa people never had a form of visual art, their chosen art was song poetry and storytelling. This meant that the abstracted animations presented to them meant very little and held almost no appeal. The consensus among the elders was that they wanted their animation to look real. When prompted to explain further it was understood that this meant that the people in the animation should look like Yanyuwa people, that the environment should look like Yanyuwa Country, and all of the culturally significant practices should be represented like Yanyuwa culture. Animation, particularly 3D animation, allowed the team to meet these visual demands and also leave enough room for characterisation for the digital cast. It was also very important that every aspect of both narrative and visuals be approved and agreed upon by Dinah and the others before progressing through the production stage.

The film was completed in 2023, but production commenced in 2017, how has the team adapted to changing expectations around sharing First Nations stories?

We can only speak specifically to the Yanyuwa experience where old people have concerns about younger people needing to know the stories that belong to their Country. As filmmakers we have understood from the start that oral traditions work differently than textual traditions and that there are variations of these stories, depending on who is telling the story. Our job has been working with old people to resolve a form of the story that all the families are happy with.

While a level of freedom was offered to the filmmakers to tell this story in a way that was both culturally respectful and also entertaining, each stage of production was under strict scrutiny by the senior elders of the Yanyuwa community. It was very important to everyone working on the film that it was seen as a collaboration and that everything was to be agreed upon by the Yanyuwa before progressing through the production. While the filmmakers are non-indigenous, they have a very long standing relationship with the Yanyuwa community and a strong level of trust is held in this regard.

The filmmakers pride themselves on their sensitivity to the importance of the content portrayed in this film, and have made every effort to ensure that it is respectful to the traditions and wishes of the Yanyuwa people. As a team we’ve had to sometimes be super responsive as people have offered sharp critiques of some of the draft animations, and these insights are so critical. Sometimes we have to let go of western expectations about storytelling and representation in regard to the final product.

There is a sense of playfulness in this story, how did you work to capture that visually?

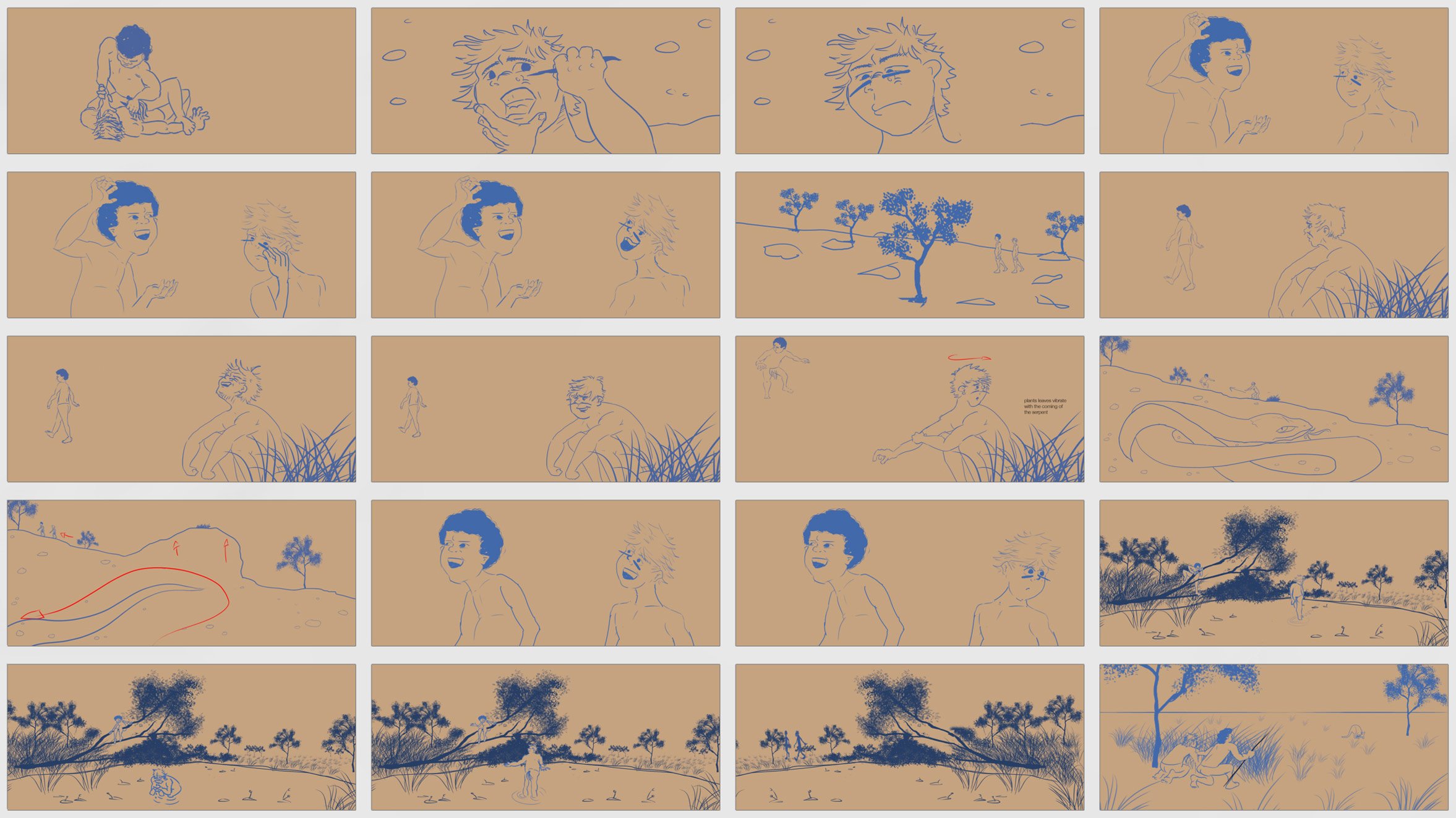

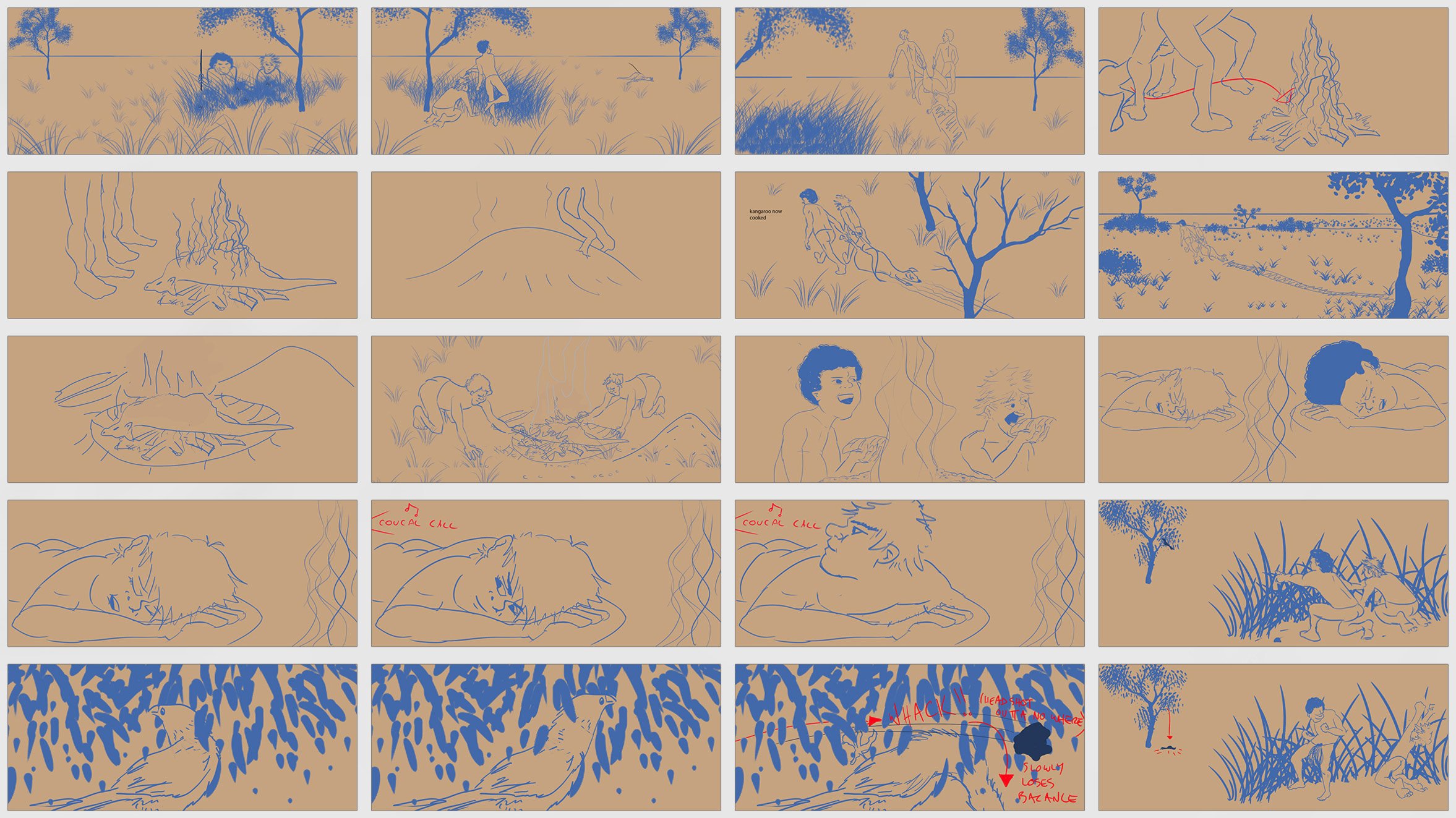

It was important to Dinah Norman that the people in the animation looked like Yanyuwa people. With consideration to this, the artists modeled the two main characters, Dambalyama and Mawurrinya, on early ceremony photos of young men preparing for initiation. These boys were then caricatured to achieve the level of exaggerated facial expression required for the animation. The design of the two cousins also represents the two common hair varieties of the Yanyuwa, one with fuzzy, wiry hair that sticks out and one with softer wavy hair. These hairstyles represent the saltwater and savannah people respectively. Throughout the film, these boys are always up to mischief, so the artists needed to be able to push the exaggerated facial features to achieve laughter, shock, fear, anger and everything in between. This was also the same with Bujimala, the Rainbow Serpent, who needed to be able to express sorrow, rage and frustration. It was important for the filmmakers to strike a balance between the levels of exaggeration and characterization needed to achieve comedic playfulness with animation, and staying true to Dinah’s wishes of maintaining a sense of Yanyuwaness and reality.

How difficult was it for the animators to create a film in a language they don’t understand, in particular the dialogue scenes?

It was fundamental that the initial script be as thorough in its English translation as it was in its native Yanyuwa. Co-Director Johns Bradley’s experience with Yanyuwa was invaluable for this, as he is currently one of the last fluent speakers having worked with screenwriter Dinah Norman for over 40 years. The script was first drafted in Yanyuwa, with Dinah telling the story to John over and over in Yanywa. This was not just fleshing out the characters and how they all interact with one another, but also the detailed significance of the events within the overall interconnectedness of the Yanyuwa Dreaming period. Once the script was drafted in Yanyuwa and agreed upon by senior Yanyuwa people, it was then translated by Dinah and John into English. This needed to be done very carefully as the english translation would become the subtitles for the final film. Beyond the actual dialogue translation was all of the extra information that was required for the animators to understand each scene and its importance within the overall story. This all needed to be conveyed with great detail knowing that the animators could not understand or read Yanyuwa.

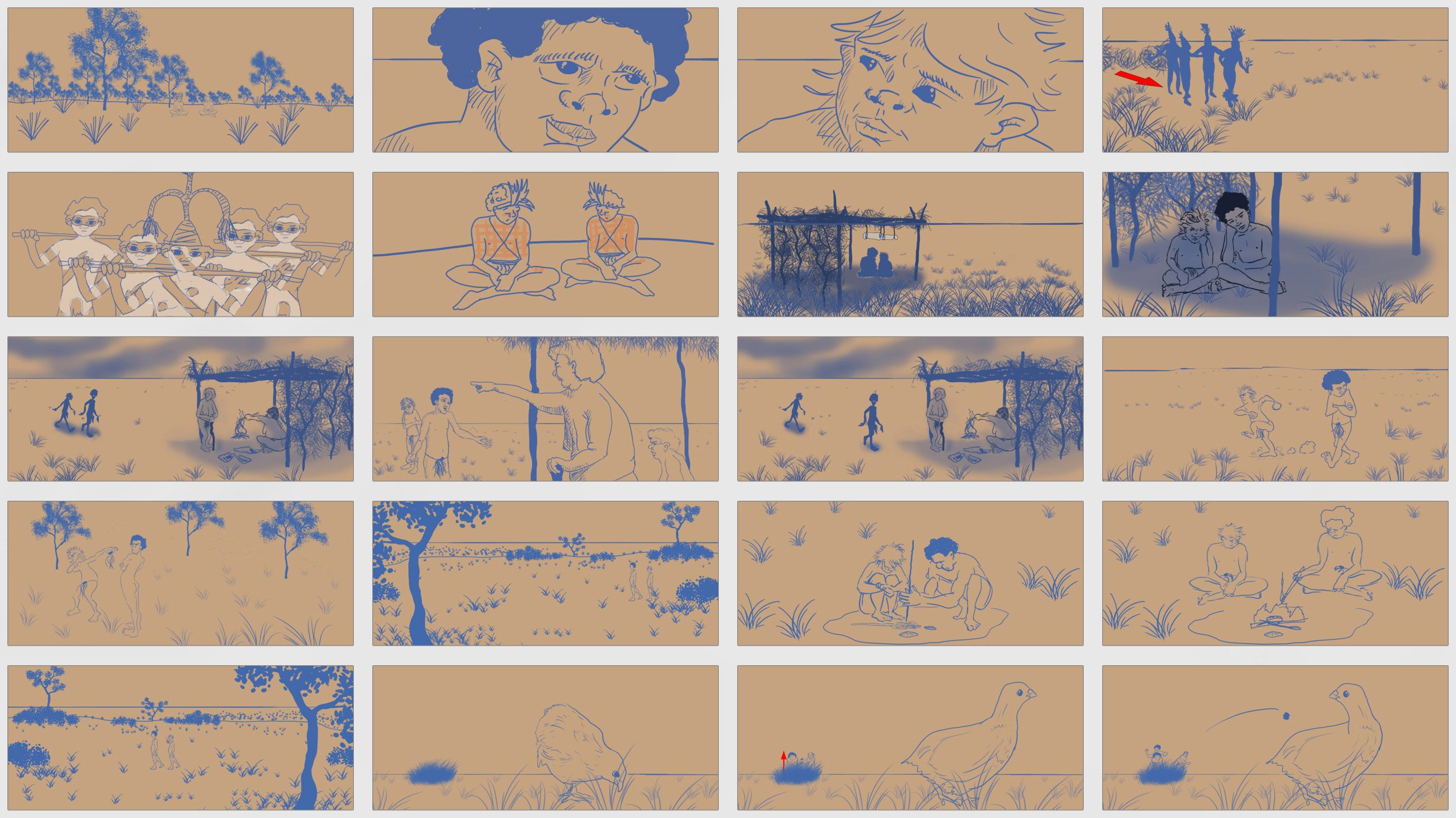

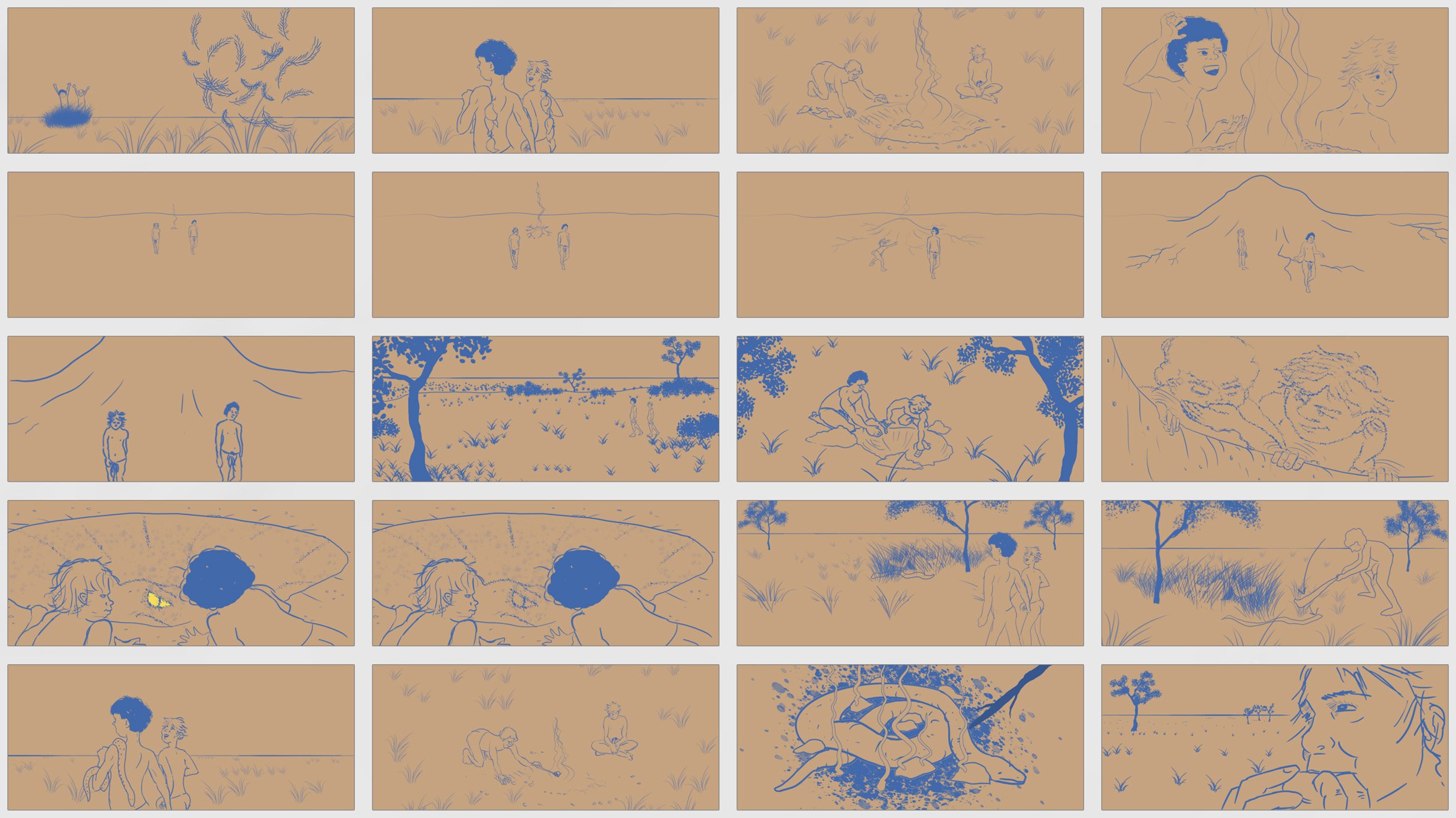

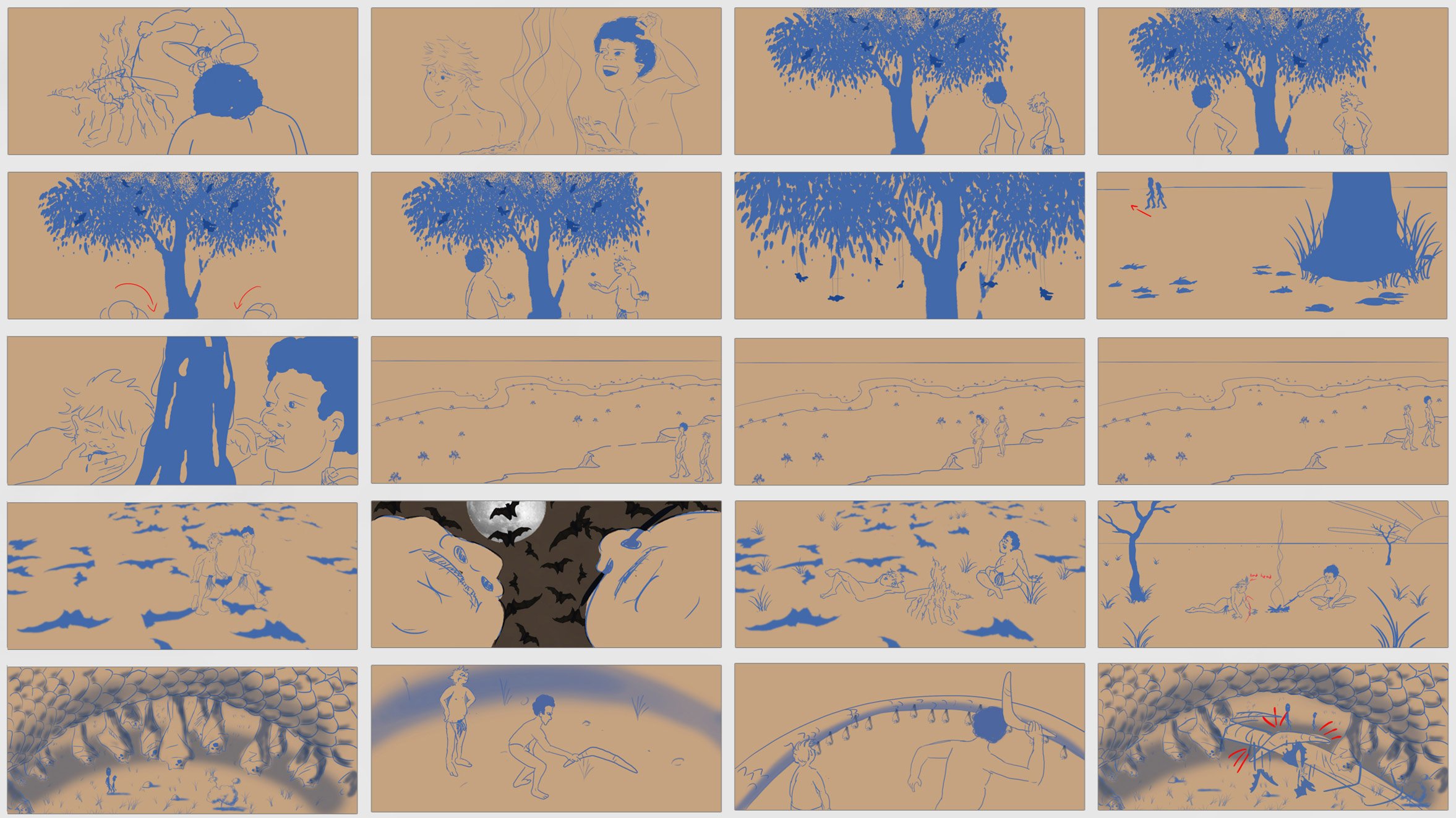

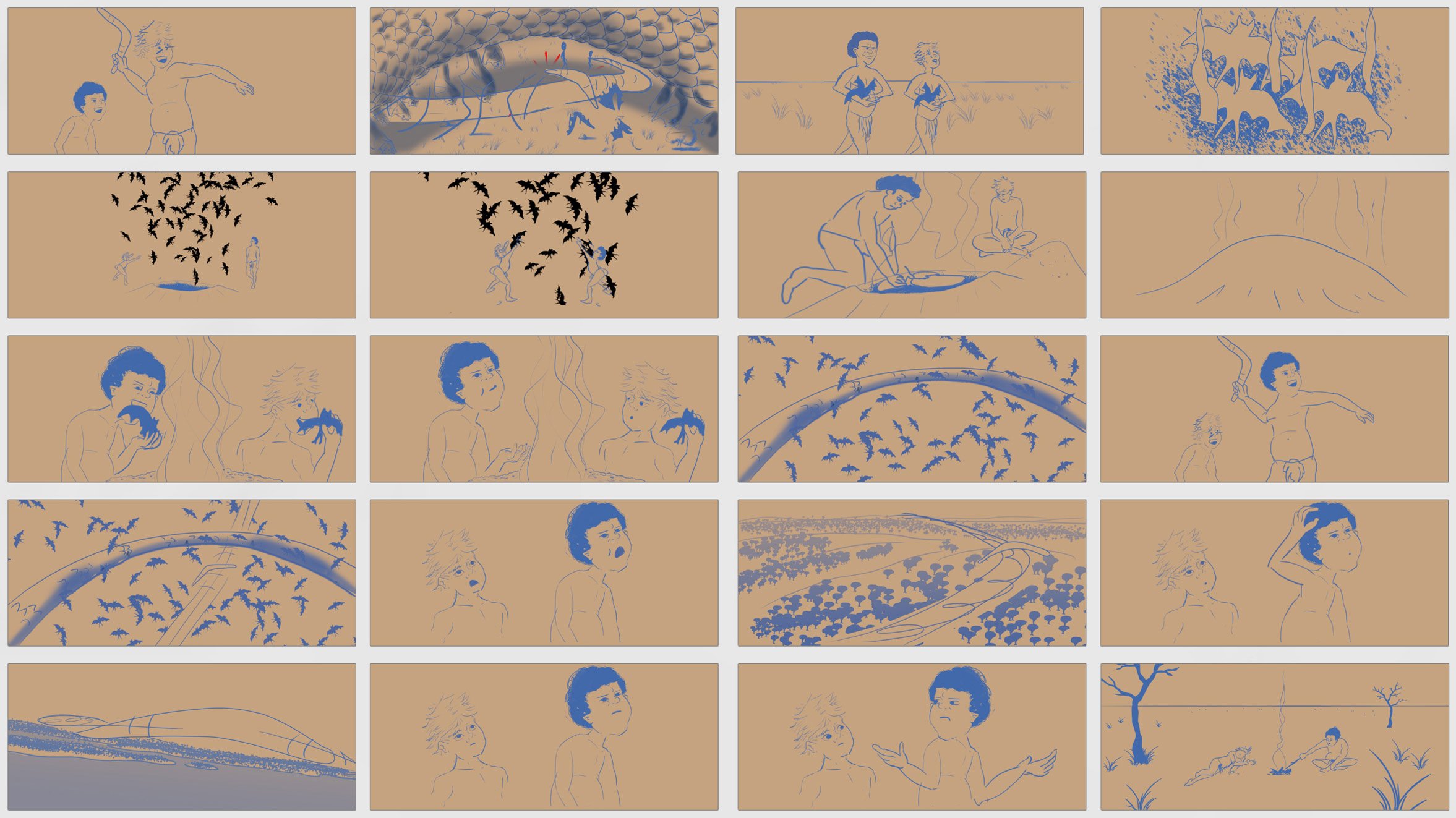

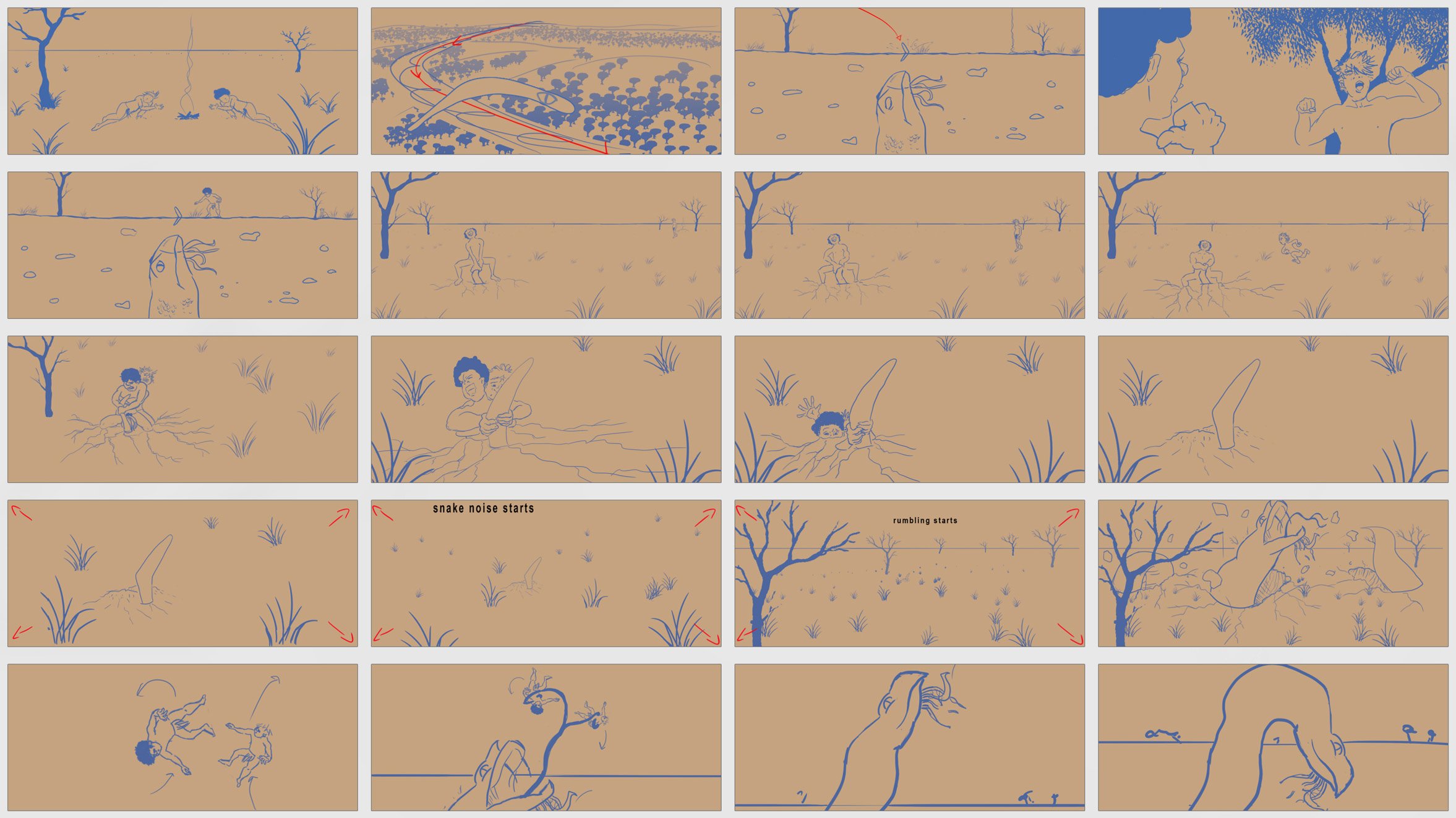

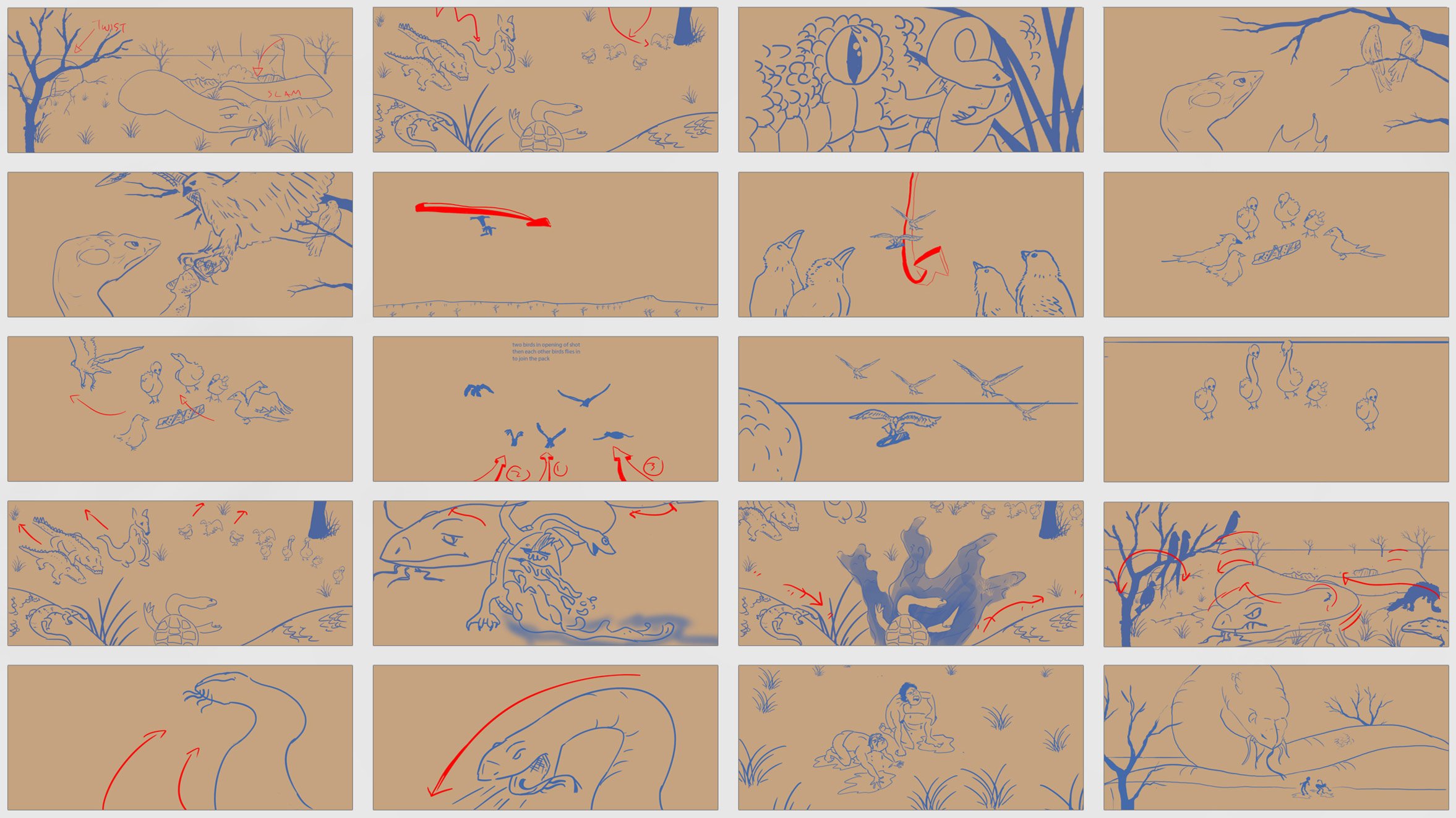

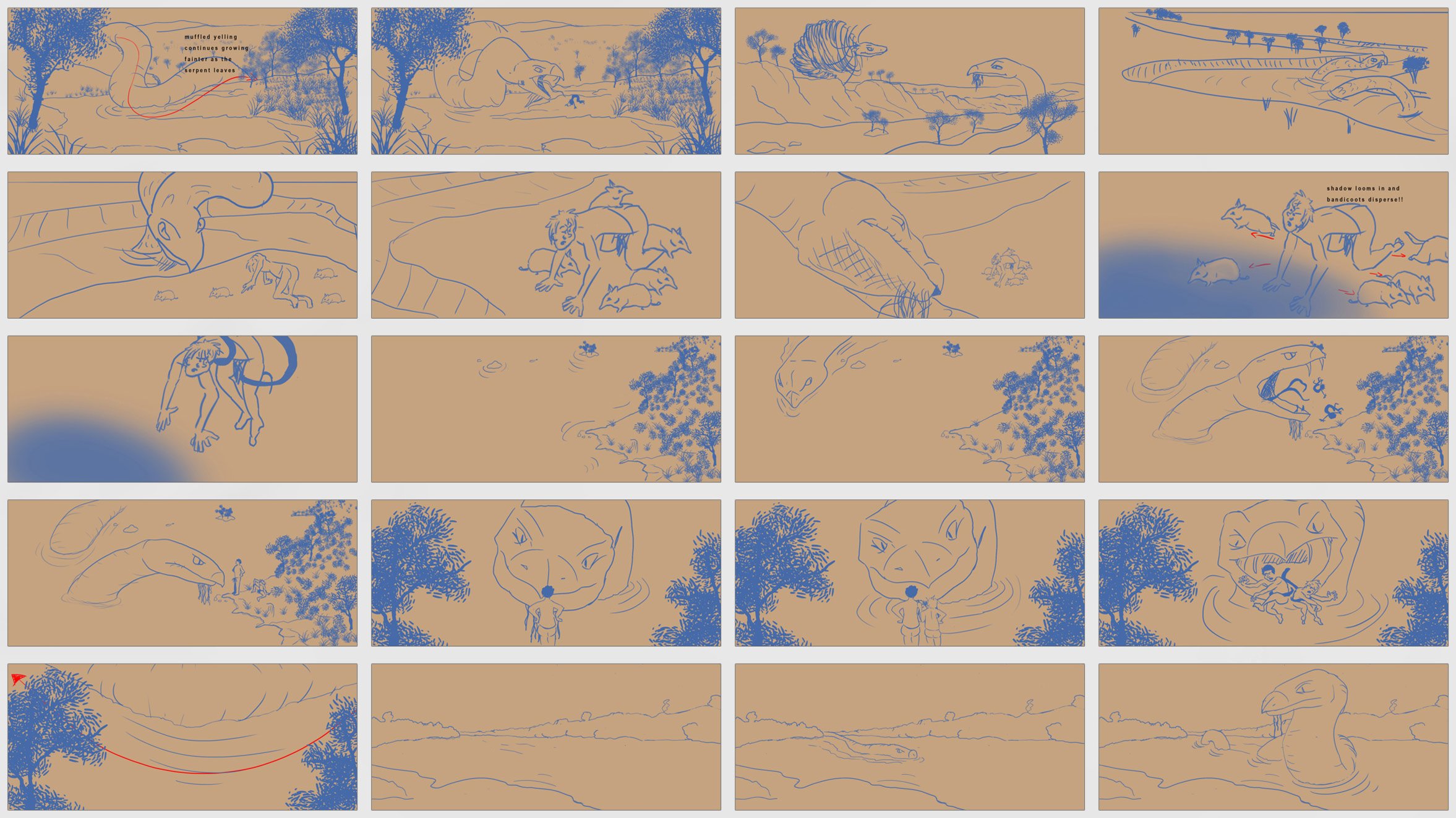

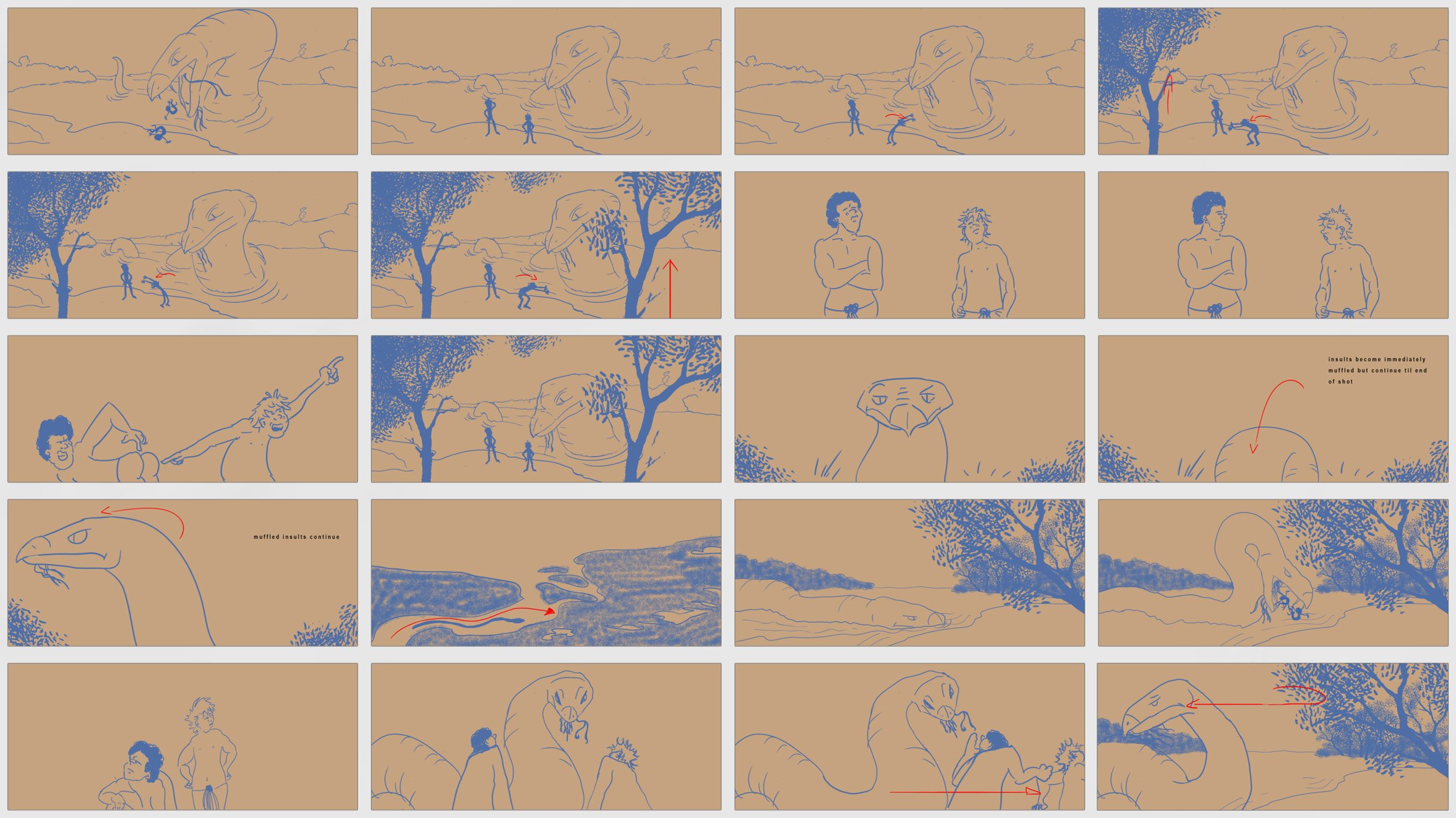

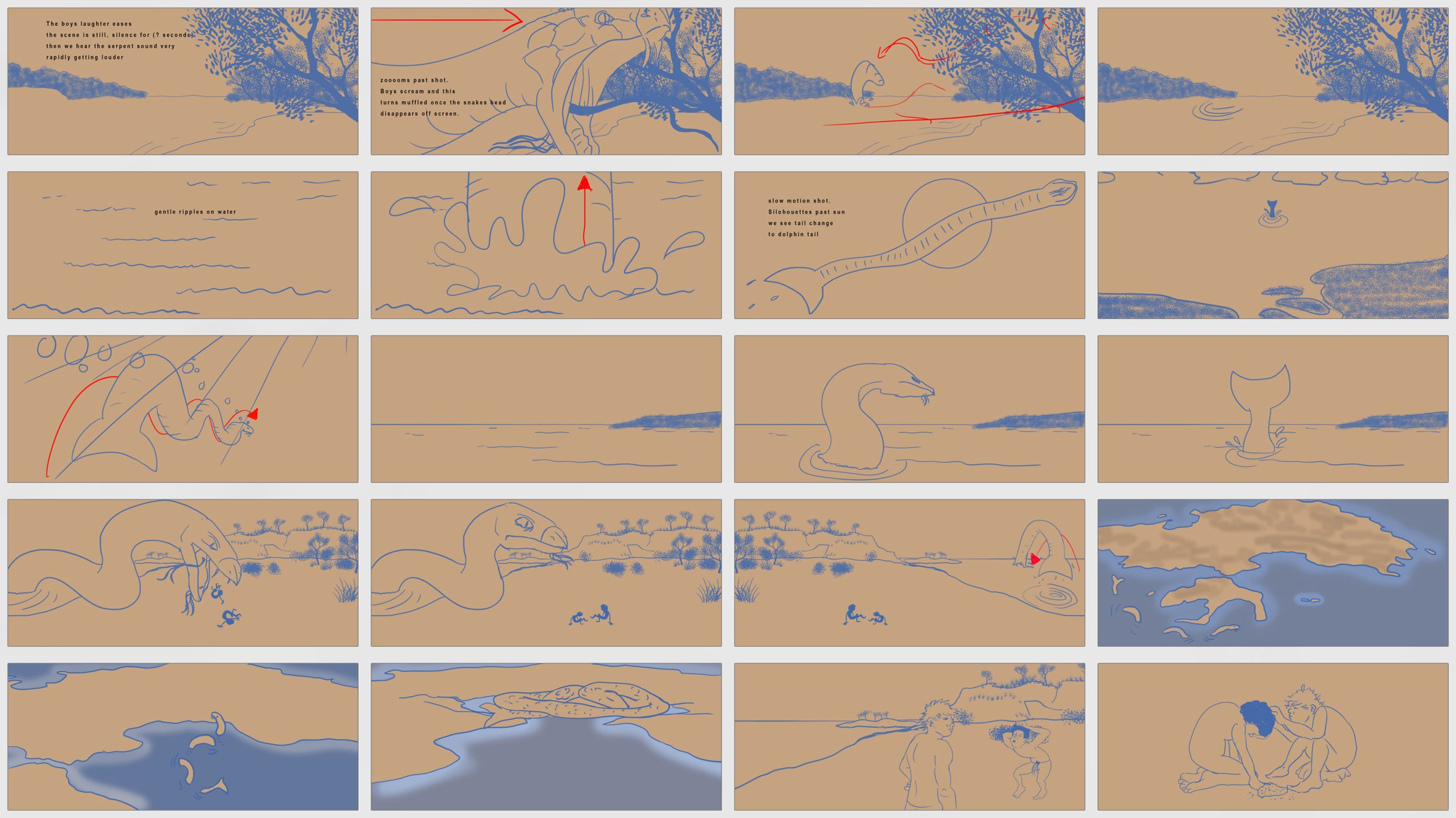

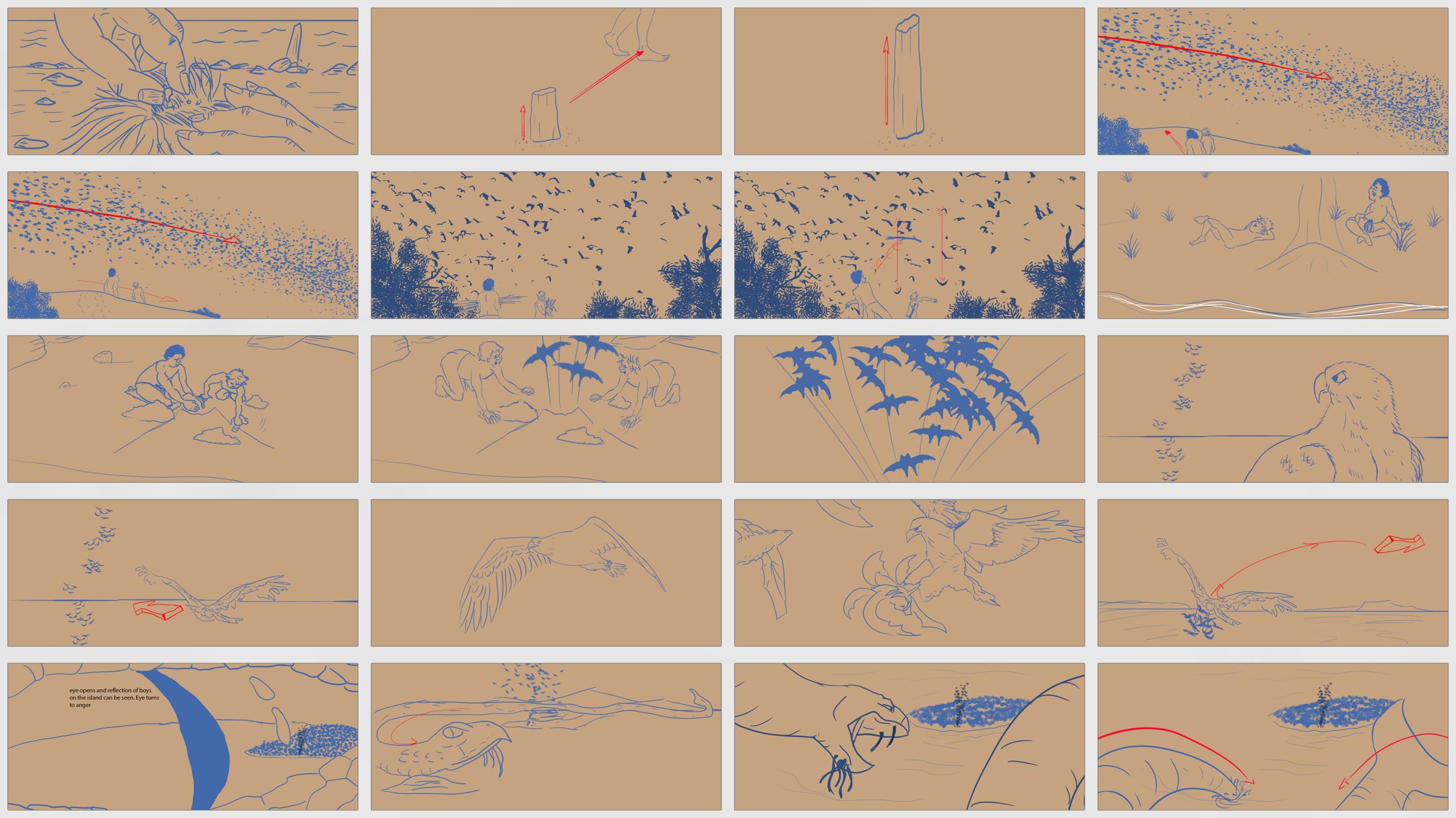

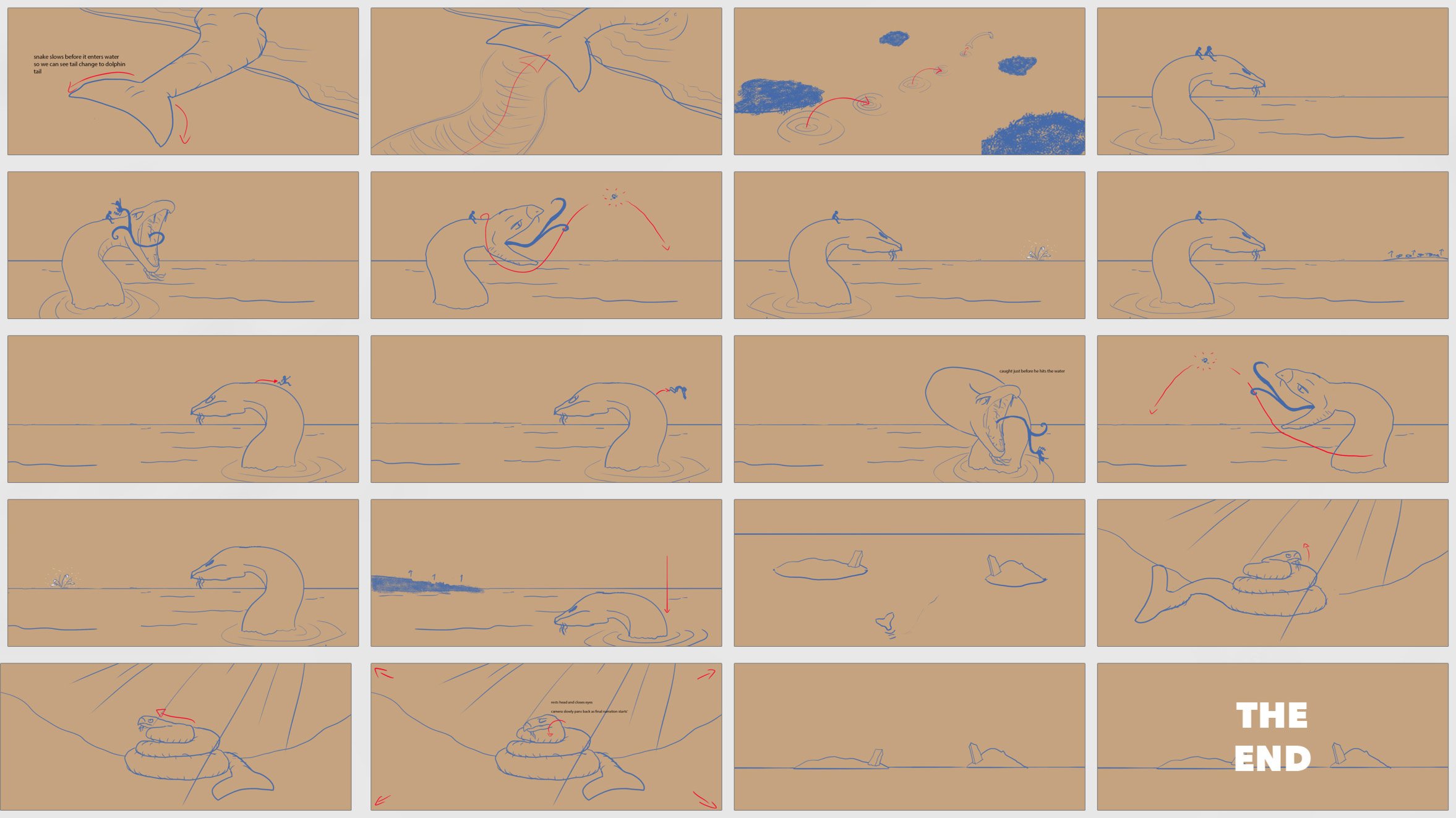

The final script, written in both Yanyuwa with English subtitles and a barrage of additional information was then storyboarded by Lead Animator Craig Martin. During this stage the animation team could flesh out the characters and key events in the film and piece together a rough draft, known as an Animatic, of the whole animation. Several back-and-forths were required between the animators and the writers where additional information was needed, or if extra lines were required to tie particular events together. It was imperative that this stage be done with the utmost care as there would only be one opportunity to record the dialogue.

While Co-Director and animator Brent D McKee had previous experience with the Yanyuwa language, his level of understanding of Yanyuwa was limited. During animation production, he had to come up with a number of techniques to make this process of believable lip animation efficient. To achieve this the dialogue in its digital format was broken down, syllable by syllable. From this breakdown, a baseline consonant and vowel library was created for each character which could quickly be copied and pasted onto the dialogue. Additional expressions could then be applied over the top to achieve the emotional emphasis for each line of dialogue. This whole process would have been very difficult for the animation team, without the in depth translation of the script into English, as well as the many hours the team spent in the early stages of production fleshing out the story and characters.

You've used modern techniques to tell an ancient story, how did that influence the way you approached the film?

On one hand the content of the film influenced what tools were best used to tell the story, and on the other, the technology allowed us to portray the events of the film in certain ways. To the Yanyuwa, this story is part of a greater anthology of narratives that woven together create the Law of their culture. The characters and the places and things they interact with are the essence of narrative that have been passed down for hundreds of years. It is this essence that the filmmakers have tried to capture, using the medium of 3D Animation as a tool. The filmmakers had been experimenting with the medium of 3D animation for engaging younger audiences and bridging the gap between generations prior to the production of Duwarra Wujara. While animation as a medium is naturally appealing to younger audiences, it also has the power to capture the attention and imagination of adults, which is imperative for the intergenerational transfer of knowledge. The mischief and playfulness of the two main characters plays perfectly with the exaggerated and caricatured medium of animation. The goal of the filmmakers was to create engagement, to spark interest in a unique culture and to create dialogue between young and old. The technological tools used to tell this story have been used for that purpose; to bring into the modern world an ancient narrative of connection and culture.

How was the voice recording for the film achieved, given the voice actors are not fluent speakers of the Yanyuwa language.

Australia is a missive country and Borroloola is a very small, very isolated town. For anything other than basic supplies you are a nine hour drive west to Katherine, or south to Tennant Creek. It is a twelve hour drive to Darwin, the closest major city. For emergencies there is an airstrip operated by the nearby McArthur River Mine. In Borroloola is the Walalungku Art Center, which is a hub for cultural activities; painting, dance and storytelling. At the back of the complex is a besser-brick building which was once used as the morgue in times of passing. The besser-bricks provide a level of sound proofing that no other building in Borroloola could provide. It is here that Co-Directors Brent D McKee and John Bradley recorded the dialogue for Duwarra Wujara.

Prior to recording, the key cast were all part of the pre-production for the film, remotely viewing early drafts and learning their dialogue parts, coached by their elders in diction and emphatic pronunciation. Brent spent a few days preparing the space, purchasing blankets to tape over windows to create a make-shift acoustic booth. Being so remote the team had to pack lite with all recording equipment needing to be compact. Recording took place over three days, with John and Yanyuwa elders Dinay Norman, Mavis Timothy, Ruth TImothy and David Issac coaching the actors through each line over several takes. In some cases the actors could make their way through whole sentences at a time, sometimes they would need coaching every few words. The elders were quick to point out when mistakes were made but the recording would continue and simply be cut up and pieced back together from the best takes.

There is much focus in the film on names of Country, yet some places are translated and others are not. Can you speak a little about the significance of the named places in the film?

Yanyuwa country has over 2000 place names, all given to the land and sea by the ancestral beings, the Dreamings. Of these 2000 names less than a quarter can be translated to a meaningful understanding. The story of the Duwara Wujara is a bit unique in having so many. What you are seeing in the film is many of the places of significance to the Yanyuwa actually being created. As the cousins travel, they interact with the world around them, with this interaction they are creating the Dreaming. These interactions happen in actual places and when marked on a map can be seen as the path of the Dreaming. (This path can be seen underneath the credits.)

When the boys dig a well and tap into the groundwater, which is forbidden in Yanyuwa law, they create a spring that is still there today, it is its own Dreaming, an important site of cultural power. This is also the case for the ground oven that grows into a giant hill, or where the boys kill the pheasant and name the place after the birds call. These places are sights for the Dreaming that runs through that Country, and in this story they are remembered largely for the forbidden things the cousins do on their adventure.

This changes once the Rainbow Serpent swallows the cousins and they travel down the river, where the places he spits them out are named but have no translation. It is not known whether the naming of those places occurred in a different story that perhaps predates Yanyuwa, or if the knowledge has simply been lost. It is a part of the great Australian myth that all names of Aboriginal origin can be translated into something meaningful. This does not mean that such names are not important, the names are still Law, they give meaning to the land and sea, as they were put in place by the original Ancestral Beings, the Dreamings.

Given the sensitive nature and cultural importance of the Dreaming period, how is funding for the production of such content sorted and who owns the final copyright?

The complexity and cultural sensitivity of the content does make it difficult to get funding for such a project. For the Yanyuwa, the Dreaming is sacred and the narratives are bound in the cultural law of its people. As such, no one person can claim ownership of the story, it belongs to the Yanyuwa people. The rights to the story and the film portrayal of the story are held solely in the hands of the Yanyuwa people of Borroloola. For this reason, the filmmakers could not seek funding from any funding body that would demand rights, royalties or ownership in any fashion. Funding for the animation had to come from one hundred percent philanthropic avenues. This film and many before it were made with very generous donations from the Alan and Elizabeth Finkel Foundation who have made significant investments into the documentation and expression of Aboriginal knowledge. The McArthur River Mine Community Benefits Trust has also provided continued support for the preservation of Yanyuwa knowledge through a number of projects, Duwarra Wujara being just one. Other generous contributions were made over the years by Monash University, Sensilab, Waralungku Arts Borroloola and the Li-Anthawirriyarra Sea Rangers Unit.